Roe v. Wade Was Never Enough

BY EMILY MONTAGUE, SENIOR STAFF WRITER, AND OLIVIA EISENBERG, CONTRIBUTOR

THE FOLLOWING IS A PART OF A SPECIAL TFW SERIES FOCUSING ON THE SUPREME COURT ABORTION RULING

By now you’ve likely heard all about the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade by our current Supreme Court. With the decision comes a slew of trigger laws, proposals, and state-by-state decisions that have a collective impact on hundreds of millions of women and anyone else who happens to have female reproductive organs.

For most of us, it feels like a violation. It feels like fear. It feels like asking a thousand questions with no good answers, and it feels like anger.

One way to handle these emotions is through education. We often feel less frightened of the things we can explain, even if those explanations are infuriating in their own right. With that in mind, we at The Fem Word have decided to take a deep dive into the recent case and all of its implications.

We hope you find this article both enlightening and helpful as you process everything that’s happening –– and prepare for the long, hard fight ahead of us.

Photo Courtesy: Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

A Brief History of Abortion in America –– Not As Conservative As You Think

Throughout much of America’s early history, abortion was a fact of life. The same was true in contemporary Europe. Both colonizers and indigenous peoples had their own views of pregnancy, birth, and termination, but most people considered it a normal and expected process that was mainly a choice exercised by individuals rather than the group as a whole.

At the same time, there were always exceptions and nuance surrounding the matter of reproductive rights. Diversity of thought was always present.

Some indigenous people, such as the Blackfeet tribe of modern-day Montana and other parts of the American West, believed reproductive freedoms to be as unalienable as any other naturally arising rights. Other tribes, such as the united Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois) tribes, have traditionally believed that a terminated pregnancy would be returned to the Creator, with the life force then being “recycled” and prepared for a different incarnation at some later time.

Other tribes and indigenous communities feel that abortion is a betrayal, a slap in the face after centuries of collective losses that included genocide, forced sterilizations, and deculturation in the name of “assimilation” within white-dominated cultures.

Early white Americans such as the Puritans of New England had their own perspectives on abortion, but many of them were quite progressive by the modern right’s standards. Abortion was only considered morally repugnant if it was done after the “quickening” period in which the fetus began to move around inside the womb. Prior to this, pregnancy was not considered inherently sacred, as the fetus was not yet a living, soul-bound “child” in the traditional sense.

Quickening can occur at different times for different women, but it’s usually within the 16-20 week window (this falls into the first to early-second trimester phase of a nine-month pregnancy). Abortions at this point were achieved through the use of abortifacents, most of which were herbal.

Surgical abortions were rare and extremely dangerous, so they were only practiced in dire circumstances. This translated to situations in which the mother’s life was in danger. Her life was nearly always the priority, as this was considered the religiously and morally correct decision to make if pregnancy or childbirth went awry.

In essence, both indigenous and early colonist perspectives around abortion were similar to those enshrined in moderately “liberal” states, which generally allow for the use of abortifacent medications within the first trimester and surgical ones in the case of complications later on.

It wasn’t until the mid 1800s that laws restricting abortion began to be passed with any regularity, and it wasn’t until the early 1900s that the practice became truly restricted or frowned upon by large swathes of society. These were times in which certain groups had vested interests in reproductive control, and many of their interests played out in hugely hypocritical ways.

While conservative whites shouted “save our race!” from the rooftops and criticized the falling birth rate as an outgrowth of women’s new, unnatural “independence,” many of these same people also supported the forced sterilization and reproductive control of non-white populations (this is a philosophy generally known as Eugenics).

In the case of indigenous peoples’ changing and diverse viewpoints, they were often a response to the traumatic circumstances imposed upon them by white governments throughout the 16th-20th centuries. This is very different than the kind of attitude commonly seen among white populations and should not be lumped in with conservative politics.

Black populations have had mixed perspectives on abortion throughout American history, and this has largely been tied to their status as enslaved people and then as an oppressed class under the Jim Crow laws of the late 19th-20th centuries.

As enslaved persons, a black woman’s pregnancy was seen as an extension of her “owner’s” rights. If he or she wanted the woman to have an abortion, she’d be forced to have one. If they wanted her to give birth, she’d be forced to do that, instead. There was little to no agency for women unless they enacted it in secret. Chewing cotton root, using wormwood tea, or seeking out other fertility inhibitors and abortifacients was a common way to subvert the will of those who claimed to own these women and their wombs.

Later on, black protestant views surrounding abortion became stricter and more politically organized. Abortion was often regarded as sinful or anti-black by both secular and church leaders. Political lines were drawn regarding the morality of abortion from a secular, civil rights standpoint as well as a religiously-based one.

Nonetheless, these views shouldn’t be lumped in with the political attitudes present among contemporary whites, even if they look similar on a surface level.

In short, abortion has been a part of American culture for thousands of years. It’s certainly not a new or modern notion, nor has it been viewed as alien or “taboo” for most of our colonial and then national history. It has, generally speaking, been seen as a personal, practical matter in which women are able to make the best and most informed choice.

The narrative that says abortion is not part of our nation’s history is quite simply false. It can easily be refuted by numerous historical realities. The Supreme Court’s assertion that abortion is somehow new or was unknown in the past is uneducated at best, and extremely misleading at worst.

Photo Courtesy: ACLU

Why Americans Made Abortion A “Thing” –– The Power Of Divisive Politics And The “New Right” Playbook

After the Civil War, America underwent radical changes in its political landscape. Platforms shifted, tensions rose, and the era of so-called “identity politics” came into full swing. This term is worth exploring before we talk about its impact on American society.

Most people hadn’t considered their political leanings to be a major part of their identities in earlier times, and one’s political opinions were generally thought to be private matters. It wasn’t something you discussed in polite company –– at least not seriously. Civil conversations between friends (mostly male) occurred, but people didn’t stand about shouting their opinions from the rooftops. That would have been extremely ill-mannered.

After the Restoration Era, things changed drastically. Politics represented more than opinions on the economy, foreign policy, or congressional bills. The South had been defeated soundly. Slave owners had seen their free labor disappear overnight, their way of life shamed, and many lost homes and fields to the Union’s infamous marches. Poor southerners were smarting from their losses, too, with many having lost what little they had after leaving home for the Confederate cause. The people were grieving, recovering, and processing everything that had happened.

The South was also extremely embarrassed. A narrative arose that championed the “Southern Way of Life” and demonized the “Northern Aggression” that had tried to eradicate it. By the 1920s, Southern organizations had raised money and erected statues honoring generals and other confederate leaders.

People started to identify more and more with their political party as a way of expression. Being a Democrat or a Republican meant being someone, and that party affiliation came with specific opinions, beliefs, and values. Politicians quickly realized that identity politics were both divisive and extremely useful. It was easy to galvanize voters using “hot-button issues” and sensationalism. Both parties utilized these tactics freely during the early-to-mid twentieth century and beyond.

Abortion is one of the issues that was systematically wielded and strengthened as a way to rally those professing to hold “traditional” values. These were overwhelmingly conservative values. Abortion came to represent every major threat to the way of life many Southerners had fought and died for –– or so claimed the subtext, anyway.

Gay rights. Women working outside the home. Civil rights reform. Divorce. Social programs. All of these things were made out to be immoral, ungodly –– a threat to freedom and an affront to every god fearing protestant and Catholic citizen out there. Abortion became a proxy for a number of these issues, and so it snowballed in importance.

Reproductive rights are a perennially easy target for those wishing to galvanize conservative and/or authoritarian elements of society.

Controversial as it may be, the fact of the matter is that every theocracy, dictatorship, and fascist state has used women’s reproductive rights as a nexus of control and ideological power. It is one of the single most reliable markers of an authoritarian movement, clearly marking the moment when a society moves away from socialism, progressivism, or values relying on individual freedom and veers toward autocracy.

By the late 1970s (and some time after a significant platform switch under FDR during the Great Depression), the Republican Party was staunchly committed to conservative values. The degree to which these values defined the Republican platform varied, but the basic premise was in place, and it would only grow in influence after the election of Ronald Reagan in 1981.

This brings us to today, and into an era in which reproductive regulation is one of the defining conservative issues. Despite being a professedly anti-regulation party, conservative beliefs almost always end up demonstrating a deep-seated need for control. Conservatives refer to themselves as the “party of morals” and the “defenders of religious (Christian) freedom,” and for many of them this includes strict regulation of things like reproduction, marriage, taxation/economic systems (in the form of protectionism), and many other matters.

So, people who oppose reproductive rights generally consider their anti-abortion stance to be a defining part of their identities, even if they don’t openly state that this is the case. Political leaders have been thriving on division for a long time, and they rarely care about the consequences until it’s too late. Neither liberals or conservatives are immune to this flaw. It crosses party lines, but in this case it is firmly a matter of conservative influence.

A Stopgap Measure –– Roe v. Wade And The Dangers Of Over-Reliance On Our Courts

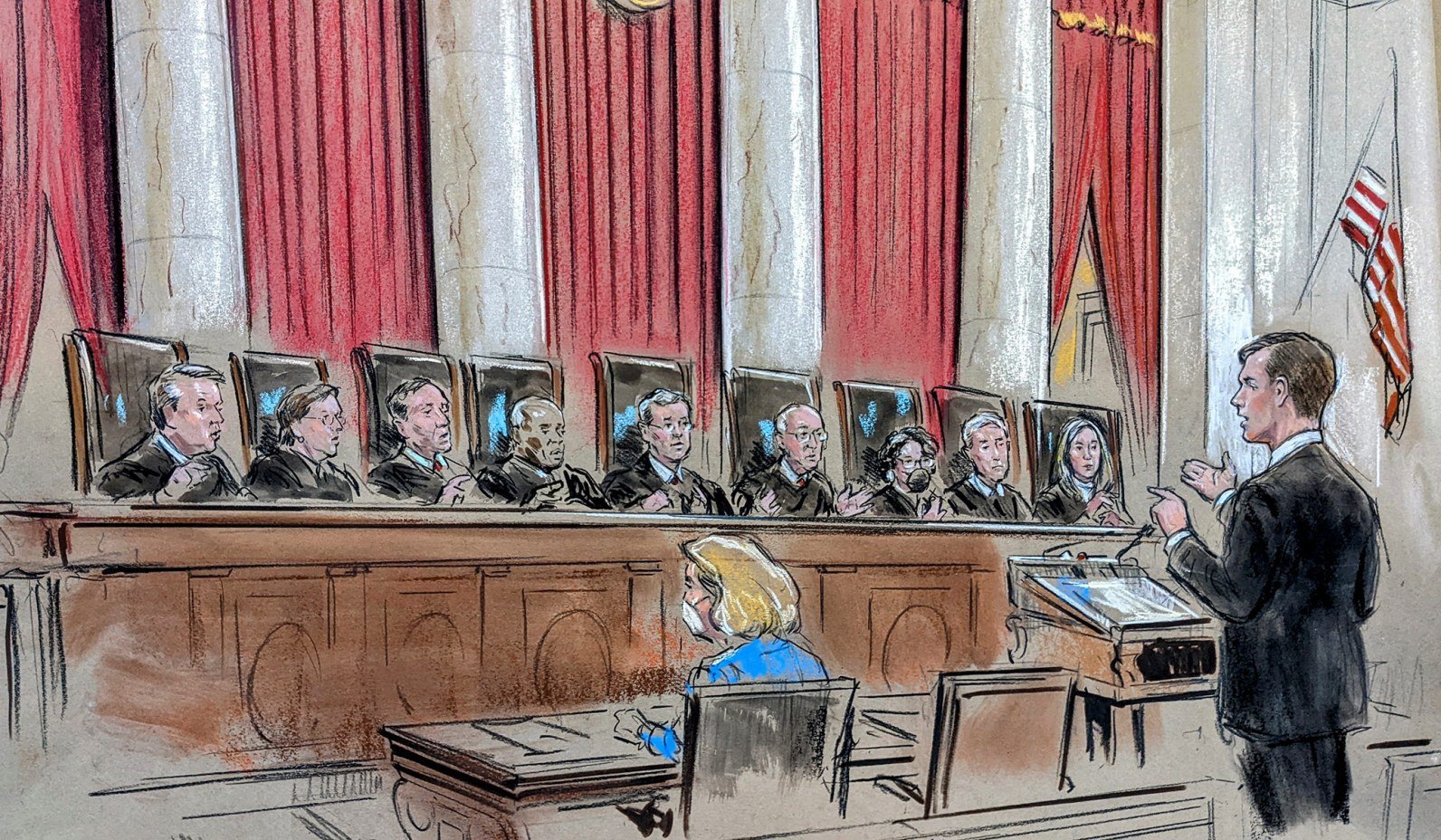

Mississippi Solicitor General Scott Stewart argue his state’s case before the U.S. Supreme Court during oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health in Washington, D.C.

Photo Courtesy: Bill Hennessy/Reuters

At the end of the day, the Supreme Court is a Court of Opinion. This is important for us to understand, because it touches directly on issues like abortion, voting rights, marriage, and privacy. In fact, it touches on every issue that comes in front of the nine Supreme Court justices and faces their verdict.

Roe v. Wade was not the first or last major court case involving American reproductive rights. Cases like Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), and City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health (1983) all expanded the right to contraception and abortion.

None of them prevented the recent ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade.

The truth is that courts aren’t meant to establish rights, but rather to debate and/or protect them. To establish a right, it has to be more than a series of court precedents. It has to be a bonafide, federally-mandated law. Without the law behind it, reproductive freedom is simply a nice thought. It remains extremely vulnerable, and as we’ve seen it is unlikely to survive a serious, politically-based shift in judicial power.

This has been noted many times by lawmakers, advocates, and judges in the past, including figures such as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She made several statements regarding her doubts about the efficacy of a decision like Roe v. Wade as a long-term protection for people seeking abortions. In one such statement she noted that:

“Roe v. Wade [...] invited no dialogue with legislators. Instead, it seemed entirely to remove the ball from the legislators’ court. In 1973, when Roe [was] issued, abortion law was in a state of change across the nation. As the Supreme Court itself noted, there was a marked trend in state legislatures ‘toward liberalization of abortion statutes”

She believed that we’d missed our collective chance to seize legislative momentum and pass codified laws establishing the individual’s right to abortion and contraception. She went on to say that:

“No measured motion, the Roe decision left virtually no state with laws fully conforming to the Court’s delineation of abortion regulation still permissible. Around that extraordinary decision, a well-organized and vocal right-to-life movement rallied and succeeded, for a considerable time, in turning the legislative tide in the opposite direction.”

Once passed, federal laws are challenging to overturn. This is especially true if a supreme court ruling follows and backs up that law. To work, the process has to be “law first, then Supreme Court decision.” Reversing that process is pretty much impossible.

Once states are handed the right to determine laws regarding constitutional issues, that issue is basically a free-for-all that can be handled by radically different state (or even county) legislatures. People living in those states and seeking the rights involved are at the mercy of their specific state legislatures. The federal government has essentially renounced its right to intervene on their behalf.

RBG was prescient when she stated that “Roe isn’t really about the woman’s choice, is it? It’s about the doctor’s freedom to practice. … It wasn’t woman-centered, it was physician-centered.” What this means is that, under Roe, individuals’ rights concerning reproductive care aren’t protected. Protections arise under the umbrella of physician-centered privacy. This privacy-based protection is easier to attack and easier to dismantle than individually-based constitutional rights.

When we step back and look at the bigger picture, the image is an ironic one. The recent loss of abortion rights is, in essence, tied directly to the passing of Roe v. Wade and the unintended consequences that decision had for our political landscape. It was never enough.

So, the question is this: what do we do now?

Photo Courtesy: Elias Valverde II / Staff Photographer

The Roe-d Ahead –– Facing Up To A New Reality And Fighting For Our Collective Future

At the moment, we’re a nation plagued by serious ideological divisions. Decades of deliberate political grandstanding, obfuscation of facts, legislative resentments, and painful incidents have led to a shared reality that looks more like a battlefield than a democratic institution.

It doesn’t need to be this way.

We can learn from the mistakes of the past, and we can remove the ammo used by identity politicians to shape and control the opinions of well-meaning Americans. Court decisions are controversial by nature. They are the perfect tool for idealogues to use against us, and this has been seen and noted many times over the course of our history.

Laws can also be controversial, but they are stronger and more enduring than opinion-based court decisions. They can stand up against a biased court, and they can champion the rights of individuals even when vocal portions of society stand against them. To establish and protect reproductive rights, we need federal law to step in and draw a line between women’s bodily autonomy and ideological pressure that can and has changed dramatically over the past five centuries.

We were founded by people who practiced and accepted abortion, contraception, and the body’s inherent right to determine when and whether it shall bear children. Just as every American is guaranteed bodily autonomy in matters such as blood or tissue donations, post-mortem status, and surgical interventions, they should also be guaranteed bodily autonomy in matters of pregnancy and reproduction as a whole.

This can only be established by the federal legislature, and then, in time, by our elected judges and the individuals who bring these matters before them. Rights begin with the law. They survive when we stand up and support those laws by voting, speaking out, and defending those laws over time.

Let’s start there. In the fullness of time, we might look back on this not as a failure, but as a simple and galvanizing lesson. Our future depends on the perspective we choose to have.

Roe v. Wade was never enough, but all of us, together? We’re more than enough to turn the tide.

THIS ARTICLE WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY OUR PARTNERS AT MONTGOMERY CARDIOLOGY! THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING WOMEN’S HEALTH, WELLNESS, AND EMPOWERMENT HERE ON THE FEM WORD <3

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of The Fem Word organization. Any content provided by the author are based on their opinions and are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, individual or anyone or anything.

The resource links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the The Fem Word of any of the products, services, or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. The Fem Word bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality, or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.