Talking 'Bout Our Generations -- How Three Successive Generations Have Changed Women's Relationship With Money

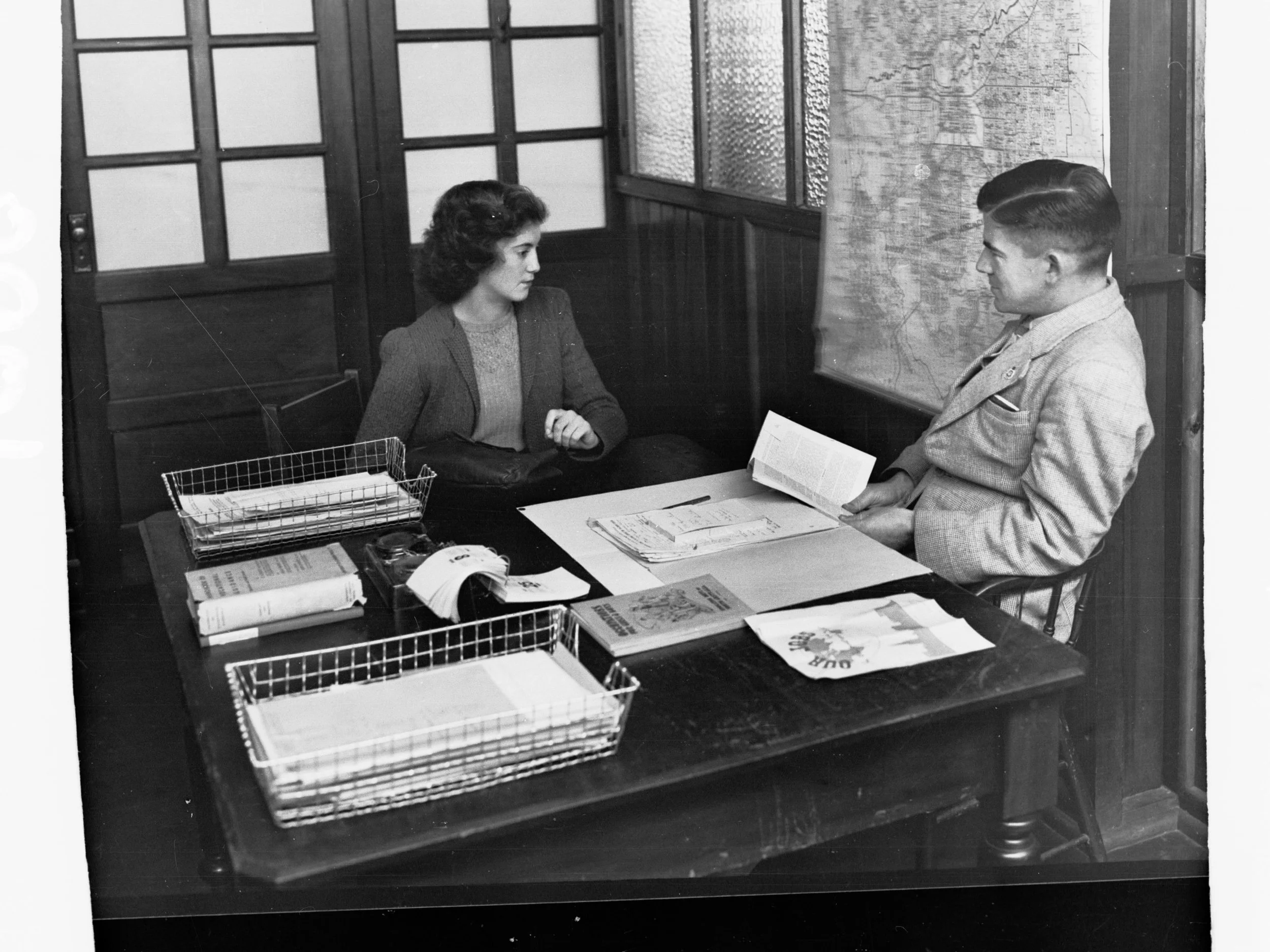

Surrounded by members of the American Association of University Women, President John F. Kennedy signs the Equal Pay Act into law (1963). At this time, banks could still deny women the right to open their own lines of credit or establish personal bank accounts. Legal protection for U.S. women’s right to credit and banking services was not established until the passing of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974.

When my grandma was born, women had held the right to vote for just fifteen years. We had the legal right to divorce, too, and the right to run for office.

At the same time, women were paid far less than their male colleagues, could be denied credit or bank accounts if they didn’t have a male signature approving of the account, were frequently discouraged from working outside of the home, and faced all kinds of other challenges to their financial independence, autonomy, and earning potential.

We tend to think of women’s rights as a given thing and equality as an assumption we’ve held for a long time. In truth, our mothers and grandmothers fought hard for the basic freedoms and protections we enjoy today.

There are many lessons to be learned from their efforts. It’s as vital as ever that we, the current generation, look back to the not-so-long-ago past and reflect on the experiences that shaped the future we would come to claim as our own.

A Woman’s Place – How Our Grandmothers Endured A System That Believed Money Was A Man’s Game

Go and open up your wallet. What’s inside? Chances are, you’ve got several cards with your name on them and bank accounts to match.

You can be reasonably sure that the banks responsible for those accounts will protect your right to your money if anyone tries to swoop in and challenge it – even if that man is your husband or father or your longtime partner. When you get your paychecks, you can go and deposit them in your own savings or checking accounts without a second thought.

No one but you can access that money without your permission or knowledge. It’s yours, and the courts will protect that fact if you ever need them to do so.

Things weren’t always so simple for women like my grandma. Like most white, middle-class women of her era, she didn’t work outside of the home. All her life, she’d been sold an image of pristine, smiling womanhood that told her, “Your place is in the house, raising kids and keeping your husband happy.”

For many generations, middle and upper class women were pressured to stay out of the workplace and within the home as housewives. Working women, who were often part of lower-income and minority groups, faced their own hurdles when it came to making and keeping their own money.

Many of us modern girls underestimate how pervasive and, yes, seductive that image was for the women of the early twentieth century. People didn’t talk about all the many downsides of relying on a male partner to care for your every financial need. The concept was sold as a gift, a privilege that allowed many women to live a life of comparative ease while their men went out and dealt with the day-to-day drudgery of work and moneymaking.

By the time most of these women were clued into the not-so-rosy reality of this arrangement, they felt trapped, and there were few ways out of their domestic prison. Norms and legal arrangements dating back to the early days of the American state remained foundational within the individual household. For every happy housewife, there were plenty of desperately unhappy wives, whether their unhappiness stemmed from simple unfulfillment fostered by a prominent power imbalance or from even more serious issues like spousal abuse and an utter lack of control over their own lives.

Even if a woman worked, as many lower and middle-class women did, it was fairly easy for a man to take and maintain control of what she earned. This was doubly true if she had children with him. Banks could and did refuse to open separate bank accounts for married women (they had to combine them with their husbands’ accounts), and institutions often denied single women the right to open accounts or lines of credit without a male co-signer who was guaranteed access to her money.

My grandfather was a good man in many ways, but power is power, and it corrupts. When he was unfaithful to my grandmother, she stayed, not least of all because she (like many other wives in her situation) could not independently afford to leave him. Many unhappy marriages have had their roots in the financial power imbalance between men and women, but it was a system few bothered to question until our mothers’ era.

To navigate this unfair financial landscape, women relied on their own cunning and resourcefulness to secure their money and keep it accessible. Some would save on household goods like groceries or furniture, then keep those savings and stuff them under the metaphorical or literal mattress, keeping the money in cash and hiding it from their husbands.

Others would negotiate a monthly or weekly allowance from their spouses, and would simply trust him to honor that agreement and not renege on his promise to share the money he earned while she kept his life running behind closed doors. Women’s methods for securing their own money were often clandestine and cunning, with the so-called fairer sex taking quiet, creative steps that offered them some small measure of dignity and protection in a world that discouraged their financial independence.

Change arrived slowly – and more recently than you might think.

Career Women and Working Wives – How Our Mothers Surfed The ‘Third Wave’ Of Women’s Rights

When my mom was born, women still couldn’t guarantee their own right to open bank accounts or lines of credit independently of a man. We didn’t secure the right to open accounts until the 1960s, and we weren’t given credit protection until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act was passed in 1974.

My mother was the consummate “working woman” of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, balancing her demanding career with all the traditionally female work of carrying, bearing, and taking care of her kid. My dad has always been an amazing father, but he just wasn’t expected to carry the same burdens that my mother did.

She was the one that school or daycare called when I got sick. She was the one who had to pump breastmilk at work, finding a private spot during breaks and trying to keep the noisy machine inaudible to her largely male coworkers. My dad, who worked in the same building, simply didn’t have to think about these things. Nothing really changed for him at work. His career went on as usual, and fatherhood didn’t necessarily intersect with that separate, working world.

Our mothers’ generations made major strides in financial equity, especially in regard to things like legal protections, maternity leave, and better pay. At the same time, the pay gap has been a persistent problem and many women — especially women of color — faced high levels of harassment, disrespect, and outright belligerence from their male bosses and colleagues…with little they could do for reprisal.

This was the era when women were told they could “have it all,” and many believed in that message. As it turned out, having it all was really just a way of saying that women had to do it all – from raising the kids to running the household and then earning half the income that kept it all afloat.

All the while, they were passed up for promotions, given lower pay, and disrespected in the offices they dutifully toiled for and provided their labor to every working day. If we’d expected respect and gratitude, well, many of us ended up deeply disappointed. Workplace protections came gradually, but what good did they do if no one was willing to enforce them? Madmen-esque corporate cultures weren’t uncommon back then, and many of our mothers had to deal with the effects they garnered on society.

I still remember my mom telling me about the extremely inappropriate comments one of her graduate-level professors made when she was working for him as a TA. He never faced reprisal for his comments — no matter how overtly sexual they were. She later faced the daily annoyances of working in an office where men formed a “boys’ club” that was supported by male managers and bosses. When men in her office made disrespectful jokes about women coworkers or even just women in general, my mom had to play along and hold her tongue just to keep the peace and make sure her workplace remained amicable. Money and the necessity of it can’t be separated from these problems. Dollar signs form the foundation upon which our behavior depends.

Working women had to face financial barriers that working men didn’t (and in many ways we still do). Women were “allowed” into the workplace, but they often weren’t given the same financial education, opportunities, or career trajectories that men took for granted.

She was barely scraping by during this period of her life. She was racking up credit card debt just to afford the basics, and that meant she couldn’t afford to make a stink about the bad behavior of people in her work environment. Her parents hadn’t taught her much about finance, and a lot of the women around her were struggling just as much as she was when it came to debt and building up a credit score (after 1989, which is when credit scores became something that everyone had).

My father, on the other hand, was a bachelor into his forties. He never had to deal with large amounts of debt. Male role models taught him how to manage his money, and he was able to buy a house, switch jobs freely, and start saving for retirement long before my mom could even consider these kinds of milestones.

Women like my mom also face the added pressure of our own biological clock; if we want to have children, we’ll inevitably have to deal with the intricacies of maternity leave vs. paternity leave. This can place a large gap in our career trajectories, and studies show that women pay a high price for becoming working moms.

As she gained experience and requisite increases in pay — an easier task in her government position than it was for many private-sector employees — my mother still had to fight to be given what she deserved for her work. She often “did men’s jobs for them,” as did most of her female coworkers, and took care of labor gaps that less competent bosses left in their projects. This phenomenon was common, as many women reading this can no doubt attest, and it mirrored the unpaid labor women were and still are expected to do outside of work.

The women didn’t get paid for this, and male coworkers who were in equal positions took it all for granted. This exhausting dynamic made her paycheck feel like a pair of golden handcuffs sometimes, and I learned a lot about womanhood in the workplace from her experiences.

It’s only recently that women from all walks of life have banded together and started talking about things like the domestic labor gap, the persistent pay gap, and the power of social norms to continue long after legal protections are offered to the disadvantaged in our society.

Modern Women – How We’re Redefining Wealth And Shifting Our Relationship To Money

It’s 2023 at the time of this writing, and wealth gaps still exist. The pay gap remains in place despite doubt and denial from certain parties. Financial abuse is a real, statistically commonplace issue that affects women from every walk of life. Women tend to perform more poorly on financial literacy tests and have less awareness of their family finances – especially regarding major issues like estate management and retirement milestones – than their male counterparts.

In short: There’s still work to be done.

Still, we’ve come a long way from our grandmother’s era, and we have every right to celebrate that progress.

Women are starting more businesses than at any other time in human history. We’re producing a greater percentage of the global GDP, there are millions of women investors and shareholders managing huge amounts of money every year, more women are breadwinners than ever before, and all in all, we’ve simply made incredible financial strides since the earlier part of the 20th century.

While we celebrate these victories and work on the still-existing problems facing the women of today, it’s important that we look to our mothers and grandmothers for perspective, wisdom, and reminders of what’s at stake.

Talking to my mom and grandma about their lives has been a gift in so many ways. I’ve learned the value of different lifestyles, different skill sets, and different models for work and career simply by taking the time to listen to their stories.

Learning from my grandmother’s mistakes – or what I consider to be mistakes – has provided me with a stronger foundation for my own financial choices. Why did she reject the chance to go to college and establish a career, instead choosing to get married right out of high school and have her first baby by 19? Is it right for me to assume that this was a wrong decision, or was it really the patriarchal norms surrounding her that made it such a struggle?

I ask questions like this, and her own regrets and non-regrets humble me, reminding me that every generation is faced with its own array of assumptions, systems, and pressures that impact their relationship to money and their potential for financial independence.

I listen to my mom’s accounts of workplace harassment and the difficulties inherent in balancing motherhood with full-time employment that didn’t make many allowances for maternity and its burdens. In doing so, I learn from all of the victories and struggles she learned to navigate while pursuing her degrees and establishing her career.

The fact that she racked up debt while negotiating lower pay and had to fight hard against entrenched “boys’ clubs” while establishing herself reminds me that these same issues still exist for us now.

My own varied struggles with financial illiteracy, anxiety, and general unpreparedness for the realities of making and retaining money during an ongoing cost-of-living crisis have opened my eyes to the particularly gendered aspects of financial adulthood in ways that are informed by my mother and grandmothers’ own experiences in prior eras. Enduring workplace harassment at two different jobs in order to keep the peace and continue to make a paycheck has made me realize just how vital it is to save and grow money.

Millenials and Gen Z are working differently, saving differently, and investing differently than our predecessors, but we still struggle with many of the same issues and financial challenges our mothers and grandmothers did (Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash).

Money is empowerment, and when you don’t have a safety net, you’re less able to confront disrespect and poor treatment. For women, these factors can compound quickly and make our financial lives stressful in ways many men don’t think about. I know women my own age who have been financially abused or drawn into abusive relationships due to their own lack of financial security. Someone in my own family, someone even younger than me, faced homelessness and was relying on an abusive boyfriend for food and shelter until we learned about the situation and were able to help her.

Money is tied into every nearly experience that defines our lives. Our financial situation determines how we approach motherhood, friendship, romance, marriage, self-love, and more. Issues like workplace harassment, financial illiteracy, abuse, and mental health are all tied deeply into our perspectives of and experiences with money.

Our grandmothers’ and mothers’ stories bleed into our own in ways we often fail to realize.

It’s all tied together, and remembering that fact is an important part of our collective progress.

This article was made possible by our partners at Foumberg, Juneja, Rocher & Co. Thank you to TJ and the team for supporting bold women in the world of finance — and beyond!

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the interviewee, and do not necessarily reflect the position of The Fem Word organization. Any content provided by the author are based on their opinions and are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, individual or anyone or anything.